Frank Warren: The solicitor's clerk, turned promoter.

Sitting down with Frank – from the ups and downs; fall-outs; being shot; and taking a punch from 'the baddest man on the planet.'

By Johnny Elderfield

As you walk into his office, amongst the signatures and one-of-a-kind collectible, what first hits the eye is a bronzed statue of Prince Naseem Hamed inscribed, "To Frank Warren, the best promoter in the world. From Prince Naseem Hamed, the best boxer in the world." A form of deference only the Prince knows how to express, in Frank being a part of his career; for it echos through Frank's boxing empire like one of the great Sinatra songs, this time in homage only to the great promoter himself, rather than love: toasting the illustrious partnership confined to boxing for generations of fighters to come.

|

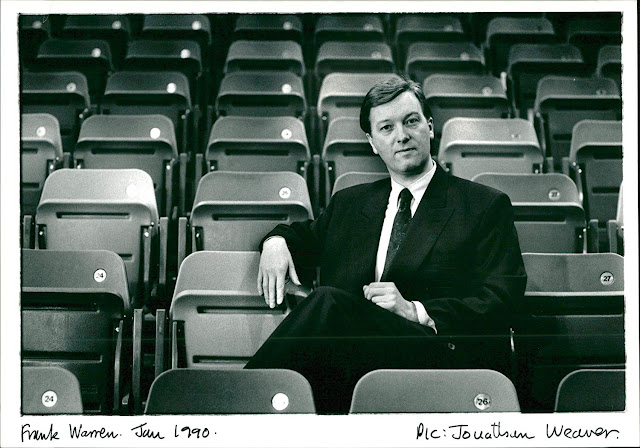

| A young Warren, photographed in January of 1990, credit: Jonathan Weaver. |

“Talk about whatever you like,” says Frank, whether that's to be taken literally, or as one of those rhetorical statements that often get thrown about when time is of the essence. At 67, Frank sits up straight, clean cut, looking sharp as ever.

With almost 40 years in the business; Frank certainly isn’t slowing down. Coming off the back of one of boxing’s biggest business deals – a joint promotion between ESPN, partnered with BT Sport to promote Tyson Fury’s next five fights through his boxing channel, BoxNation – worth a reported £80 million, he’s quite an intimidating but gentle figure.

Frank Warren’s Queensberry Promotions signed a multi-year agreement with ESPN, BT Sport, and Bob Arum’s Top Rank boxing. ESPN will become the exclusive US broadcaster for his shows. UK and Ireland fans will watch the Queensberry Promotions’ fights on BT Sport and BT Sport’s Box Office.

Round 1: the bell rings…

From a humble start, Frank left grammar school at the early age of 15. His introduction to boxing wasn’t an easy ride, certainly not as easy as some of his competitors, particularly those in more recent times with whom he's had some well-publicised feuds.

J Tickle & Co was where Frank got his first start, not in boxing but as a busy solicitor's clerk in Southampton Row, learning a trade in the heart of London. It was here, briefly, where Frank probably realised the nine to five rat race wasn’t for him.

He started early in the fight game, promoting unlicensed fights in the late 1970s at the age of 20 across the capitol.

“I had a cousin – second cousin, on my uncles’ side – his name was Lenny McLean,” says Frank, sat firmly at his mahogany desk, with an array of memorabilia, expensive, shiny, (and mostly all Arsenal) filling his large office.

Lenny McLean, the fierce and ferocious street fighter, known to many as the Gov’nor, was then London’s most feared bare-knuckle boxer.

McLean was notorious in the 1970s, renowned in London for his reputation as a fierce brute, and two fists, each of which often put fear into the eyes of the hardest of men.

“In those days they called them unlicensed fights, but they weren’t unlicensed. The fact was they weren’t licensed by the British Boxing Board of Control, instead, they were licensed by the local authorities. I got involved with him [Lenny McLean] over a couple of his fights, successfully. Then the British Board of Boxing Control invited me to take out a license and promote fights regulated by them, as well as by the local authorities.”

Frank believes he could have done as many as 20 'unlicensed' fights before he was affiliated professionally with the British Boxing Board of Control.

McLean’s credibility as London's hard-man ended up transcended the streets. So much so, Guy Ritchie featured his gangster persona in his 1998 film: Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels – by which time Frank had become the biggest promoter this side of the Atlantic.

Frank is quick to quash any form of connection being made between him and the underworld. He is a professional: a veteran of the fight game; a Hall of Famer with 40 years’ experience behind his name; a name now synonymous with British Boxing.

Before then there wasn't a script promising promoters could read from. Today you’d have to obtain a university degree, get yourself into some amount of debt and obtain at least several years worth of work experience to do anything worthwhile: by the end you might be able to make a good cup of tea. Frank though, he came from the school of hard knocks, forging his own career in a game he loves, taking no prisoners along the way, manifested out of pure passion.

Frank believes his first big break in boxing came in February of 1982. He was promoting British super-lightweight champion, Clinton McKenzie, born in Jamaican, he grew up in Croydon, South London. At only 5’,7” McKenzie's strength was remarkable for a super-lightweight fighter.

McKenzie was making the third defence for his British title against Steve Early. Early was a veteran in British boxing, with 23 fights, 21 wins by way of 12 knockout, and only two losses to his name. Frank's first professional promotion made for a real domestic grudge match.

Although it went a long way, it wasn't the match making that furthered Frank's career: the bout was broadcast to a nation.

“I think anything you do with boxing, if you don’t have TV coverage, it’s not going to work, so I think my biggest break was getting that TV coverage,” says Frank.

This particular show was broadcast by the BBC, a one time occasion for Frank.

McKenzie was victorious against Early. The Jamaican's strength eventually costing the veteran, winning by way of knockout in the 4th.

The ten-count: "Everyone has a plan until they get hit." – Mike Tyson...

Regarding successful sport. Boxing is no exception to the rule: television sells – networks tie themselves to fight stables and rely heavily on promoters like Warren and Hearn to create spectacular events for broadcast.

BT Sport use Frank Warren’s Queensberry Promotions with fighters like Tyson Fury, the WBC, Ring and Lineal heavyweight champion of the world; Carl Frampton, former three-time world champion; and rising star Lyndon Johnson, the Commonwealth light-heavyweight champion.

Sky Sports, meanwhile, work with Matchroom Sport, where Eddie Hearn took over from his father, making a great success of their boxing division in the last 10 years. Since then Matchroom have had the crème of the crop, drawing in big names like Anthony Joshua off the back of Team GB's successful 2012 Olympics, in London. Matchroom Sport's promotional deal with Sky Sports and new U.S online streaming service, DAZN – founded in the UK – have been tempting fighters to jump ship.

Arguably Britain's most skilful fighter, recently did just that, leaving Queensbury promotions for Matchroom Sport with just one aspiration: getting in the ring with Canelo Alvarez – a fight that could reportedly earn him $20 million.

Standing toe-to-to: "The hero and the coward both feel the same thing. But the hero uses his fear, projects it onto his opponent, while the coward runs. It's the same thing, fear, but it's what you do with it that matters." – Cus D'amato

Before the surge of popularity in boxing, where most events would have been held in sports halls, big fights now fill stadiums like Wembley, taking the sport back to the golden age, like when Ali met "Enry's 'Ammer" in 1963.

|

| "Enry's 'Ammer," reducing Ali to the canvas. |

On Frank’s right stands a piece of iconic memorabilia, roughly eight inches tall and beautiful, protruding over everything else. An ebony statue of the Greatest, Muhammad Ali.

“There is always a shock in seeing him again. Not live as on television but standing before you, looking his best. Then the World’s Greatest Athlete is in danger of being our most beautiful man, and the vocabulary of Camp is doomed to appear,” wrote Norman Mailer in The Fight.

It would then have been a disappointment, to see anything other than the man who, according to so many, had transcended not only boxing but sport itself. But there it was, Muhammad Ali, in all his glory, a champion for all of time, overseeing the decisions for British boxing talent, some good, most great.

Frank speaks about the early days of his career as a promoter, discussing the ambiguous nature of what he calls, “the cartel of boxing.”

“I made that fight [McKenzie vs Early]. It was very difficult. Because the fighters were involved with the then cartels of boxing who used to run the shows in Wembley and the Royal Albert Hall,” says Frank.

The cartels of boxing were a legal, in-house stable that included the likes of Alan Minter, Charlie Magri, John Conteh, John H Stracey, and Jim Watt amongst others.

They had monopolised the market for decades through their exclusive access to the two major London venues and their exclusive association with the BBC.

At the time there were only a handful of channels operating, not like now, with channels dedicated solely to boxing, alone. The BBC, with their government funding could afford to put money aside for boxing on occasion, it was with the cartel that they could facilitate this through.

The cartel was run by Mickey Duff, a boxer who retired at 19 in the 1940s, becoming the fight game’s most respected and feared promotor.

“Duff took control of British boxing in the 1970s when he formed a legal cartel with Mike Barrett, Jarvis Astaire and the boxing trainer Terry Lawless. The cartel, dominated by Duff’s boxing brain, enjoyed a 30-year monopoly with the BBC and had a hold on the best and biggest venues in London,” according to Steve Bunce, of the Independent, on the 14thof March 2014.

That was, until Frank entered the game.

“Just me being a pig-headed bastard,” says Frank.

Frank had broken the so-called cartel of boxing through a succession of fights that included bringing Joe Bugner back into the game. The cartel, it seemed, had become stale. They had had little to no competition until Frank entered the game. Their operations had become outdated and the viewing public and the sport demanded more.

And more was what Frank gave them.

At the time, live boxing wasn’t a common thing like today, where fighters like Fury or Joshua are built up over a number of weeks. No, before what is now thought of as common practice, didn’t exist.

“Fights at Wembley or the Royal Albert Hall were on a Tuesday night. The main fight highlights were shown the following night on what was called BBC Sports Night. Then on a Saturday, there was a show called Grandstand which showed the undercards,” says Frank.

Frank is adamant at that time the sport was going down the pan. He didn’t have the clout he has today, nor the capital to take the risk but shore enough he has a major affect on how British boxing is perceived today.

“I didn’t see the legality of how that was being right, and I didn’t see it benefiting the sport,” says Frank

“I mean, you can go back to a time when boxing was on in the national sporting club in London – and you go back then – people were not even allowed to talk during the fight.”

During the 1970s, boxing felt very different.

“You were only allowed to applaud,” says Frank.

But Frank knew exactly what was needed: live TV coverage of boxing in the UK.

“I had to threaten to take the Boxing Board of Control to court. On one show they withdrew the official, that was up until the afternoon of the show, and then we were going to go through an injunction to stop that until they backed down. That’s what we had to do to get live boxing on TV,” says Frank

“They felt that live boxing on TV would affect the gates, we proved that it was totally different.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Frank went on to break the cartel, sign a ground-breaking live television contract with ITV and build a formidable stable over the ensuing years featuring some of British boxings biggest names, including Eubank Sr, Benn, Calzaghe and Prince Naseem Hamad.

“There was a fear that live coverage of sport on television, whether it be boxing, football, or even rugby would seriously damage attendances at stadia,” says Trevor East, who was head of sport at ITV when Warren rose

How wrong all the sporting bodies were in the 80s’.

“You only have to look at the TV schedules today to see what an important role live sport on TV plays in our daily lives,” Trevor East continues.

Not only have attendances grown but sport has been financially rewarded accordingly ever since.

Frank Warren is still there, still at the top, still making £80m deals.

Comments

Post a Comment